The Crow Folk Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Join our mailing list to get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For Claire and the magic she makes.

June, 1940

War rages in Europe. The defeated British Expeditionary Forces and their allies have retreated from Dunkirk, and France has fallen to Hitler’s Blitzkrieg. In Britain, food is rationed, and children are evacuated from cities to the countryside to escape the coming bombardment. With so many men away fighting, it falls to the women on the home front to keep the country running. The Women’s Land Army helps on the farms, the Air Raid Precaution wardens watch the skies and the Women’s Voluntary Service supports them all. Men too old to be conscripted sign up for the Local Defence Volunteers (soon to be known as the Home Guard) and prepare for invasion.

Meanwhile, in a quiet village in rural Kent, strange things are afoot…

PROLOGUE

A field in England

Under a sunset sky streaked with pinks and yellows, a scarecrow stands alone in a field. A sorry sight in a tatty red gingham frock that was once someone’s Sunday best, she has a sack for a head, buttons for eyes and stitches for a smile. Draped in a musty old shawl, she hangs on her cross like forgotten laundry. She has a name, Suky, but her mind is as empty as her pockets.

Across the tilled soil comes the metronomic clonk of a cowbell.

A figure stalks over the field, swinging the cowbell like a priest with incense, but he moves unnaturally, limbs all herky-jerky. His dusty dinner jacket billows behind him, his scuffed top hat at a jaunty angle. Jackdaws warn him off with salvos of kar-kars, but he keeps coming. His head: a pumpkin of prize-winning orange. His smile: a jagged sawtooth. His eyes: triangles of black.

The jackdaws know enough to fly away as he approaches, leaving Suky alone with him. He rattles the cowbell some more to ensure they don’t come back. The echo dies and there is only the gentle rumble of the breeze. The air is summer-sweet, the soil flaky, the sky turned blood-red. Pumpkinhead slips the cowbell into his dinner jacket as he moves closer. He circles Suky, his feet skipping like a dancer’s, then he cradles her sackcloth head and whispers words in a language not heard since his kind were banished.

The words sink inside her, filling her to the brim. It takes time. Pumpkinhead is patient.

Suky shudders, her straw stuffing rustles and she looks up, a light in her button eyes.

‘That’s it,’ Pumpkinhead tells her. ‘Here, let me help you.’ He takes a folding knife from the band in his top hat and cuts her bonds.

Suky’s head darts around. A frightened newborn.

‘You are free, sister,’ he tells her. ‘We all are.’

A jangling and clanging comes across the field. Suky looks to the horizon where a dozen or more scarecrows dance in a parade towards her.

Suky’s sackcloth head creaks as her stitches form a smile.

1 WYNTER’S BOOK OF RITUALS AND MAGIC

Faye Bright’s dad once told her the old hollow oak marked the centre of the wood. She was six at the time and they had been walking Mr Barnett’s dogs when they came across the tree. Dad said it was the oldest in the wood. Young Faye half expected to find a fairy-tale wolf peering out from behind it.

Faye was seventeen now. There weren’t any wolves in Kent. And the hollow oak was as far as she could get from prying eyes. That was where she would open the book for the first time.

Faye had found the book in a trunk of old knick-knacks when she and her dad had been clearing out a corner of the pub’s cellar. They were looking for bits of old scrap metal for the ‘Saucepans for Spitfires’ collection run by Mrs Baxter when Faye unlocked the trunk tucked in the shadows behind the ale barrels. Inside was a box of letters, a hairbrush with an ivory handle, a few cheap necklaces and earrings, a cracked gramophone record of ‘Graveyard Dream Blues’ by Bessie Smith and this leather-bound book.

Faye’s dad Terrence was busy sorting through a box of dull cutlery when she took the book from the trunk. It was ordinary enough to look at. Red leather, much like a ledger or a diary from a stationer’s, and the cover and spine were plain with no title or author. All the same, a voice at the back of Faye’s head told her she should keep its discovery to herself. She opened it to the first page. The words scrawled there in Indian ink nearly stopped her heart.

Wynter’s Book of Rituals and Magic by Kathryn Wynter.

Wynter. Mum’s maiden name.

And then, beneath that, and written in darker ink:

To my darling Faye, for when the time is right.

Faye closed the trunk, hid the book under her dungarees, told Dad she had ringing practice and legged it.

Faye didn’t want to open the book in the pub, she didn’t want to open it in the village, she didn’t even dare open it in the privacy of her room. She had to get as far away as possible from other people, which was why she made a beeline for the hollow oak in the middle of the wood.

All the road signs had been removed to befuddle invading Nazi spies, but Faye could have cycled this route blindfolded. She pedalled from the village along the bridleway by the Butterworth farm, over the Roman bridge and into the wood until the path surrendered to tangles of ferns and bracken. She left her bike leaning against a silver birch and continued on foot, all the while thinking ahead to how she would explain the book in her satchel if anyone were to see her reading it.

The ancient wood had shrivelled over time, eaten away by farming, roads and housing. Now it was little more than a few square miles of ancient oaks, yews, pines, birches, beeches and alders packed together.

Explore it long enough and you would reach chalk cliffs and the coast, but the wood’s roots clung onto Woodville. The village sat snug on its border, and the two existed in a sort of truce. The villagers took only what they needed, and the wood tolerated their odd little rituals, like when they pootled about in groups with maps and compasses and got lost, or when they brought their dogs to chase squirrels and piddle on the trees. It was perfectly happy to let the girl in the dungarees with the nut-brown hair and big round spectacles wander along its hidden trails in the fading light. Had the wood known what was to follow, it might have put a stop to her there and then, but it was getting complacent in its old age.

Faye crossed the stepping stones of the glistening Wode River and hurried up the muddy bank where she had once found a flint axehead. The local vicar, Reverend Jacobs, reckoned it dated back to the Stone Age when folk first settled Woodville. He had put it on display in the church next to the few bits of Saxon clay pots he had found when hiking with the Scouts. Faye briefly considered pursuing a career as an archaeologist, but two summers ago one of the Scouts, Henry Mogg, had told her girls weren’t hardy enough for outdoor pursuits, so to prove him wrong she kicked him in the shins and got thrown out of the Girl Guides for unruly behaviour.

She was too old for them anyway. Seventeen and ready for anything. Even a war.

The summer sun was dipping below the treeline when Faye arrived at the hollow oak’s clearing. She shuffled around to make sure there was no one about, catching a flash of red, green and yellow as a woodpecker swooped between the trees. Confident she was alone, she sat at the foot of the tree. Centuries old, the oak leaned over Faye like a curious onlooker. Its gnarled roots reached through the soil, twisting around her like a nest as she got comfy.

Faye leafed through the pages of the leather-bound book.

‘Blinkin’ flip, Mother,’ Faye said to herself in an awed voice.

On every page were pencil and charcoal sketches of symbols, runes and magical objects, alongside watercolours of strange creatures that couldn’t be found in any zoo. Around them were notes scrawled in ink. A few times, the notes were made in steady cursive handwriting, but it was mostly in smudges and smears scrawled in flashes of terrified inspiration.

This wasn’t like any book that Faye had ever read before. She enjoyed detective novels where some clever clogs solved a murder. There was none of that here. Here were rituals, magic, monsters, demons and, for some reason, a recipe for jam roly-poly.

She flicked through the pages until the sketches and words became a blur. A scrap of notepaper slipped out. Faye snatched it up before it hit the ground and turned it over.

‘Bloody Nora,’ Faye said, not quite believing what she was seeing.

Eight handwritten columns of numbers filled the page, with lines of blue and red ink zigzagging between the numbers. Few folk would know what they were looking at; some might suspect a code, but Faye recognised it immediately.

This was a ringing method for church bell-ringers.

Eight columns meant eight bells and the red and blue zigzags were the working bells. Faye rang at Saint Irene’s every Friday and Sunday, as she had done since she was twelve. Her mother had been a ringer, too.

Mum had gone and created her own ringing method.

And it had a name. At the top of the page, Faye’s mum had written the word Kefapepo. It didn’t sound like a ringing method. They had odd names, to be sure, but they were usually called things like Bob Doubles, Cambridge Surprise or Oxford Treble Bob, but not this Kefa-wossname nonsense. And it was a peculiar method, too. Faye tried to play it in her head, but something wasn’t quite right.

Magic, rituals and bell-ringing.

And jam roly-poly.

Beneath the method, Faye’s mother had written more words: I break the thunder, I torment evil, I banish darkness.

‘You what?’ Faye muttered to herself. ‘Oh Mum, what are you babbling on about?’

Faye had been four when her mother died. Old enough to have memories, even if they were ghostly. Details would come to Faye in little flashes at unexpected moments. The scent of rosemary sparked a recollection of helping Mum in the garden when she was a toddler. The blanket on Faye’s bed reminded her of kisses goodnight. Mother was comfort and happiness.

Which was why Faye was so angry with her.

Faye knew it was wrong. It wasn’t Mum’s fault she died so young – diphtheria wasn’t picky – but any mention of Mum made Faye’s blood boil. All those years growing up without her, all those birthdays and Christmases and summers, and all the things they would never do.

And so Faye shut her away. Mum was in the past, a stranger, a fuzzy memory. Faye was all right with that and got on with her life.

Turned out that Faye had been fibbing to herself. When this book fell into her lap, Faye stupidly allowed a little flicker of hope to flame. Finally, there might be some clue to who her mother really was. Finally, that big gap in her heart would be filled.

Sadly, if this book was anything to go by, then her mother was either a witch or off her rocker.

Faye read through the pages from back to front, then front to back, mesmerised by the words and pictures, wondering why her mother had made it, and why her father had never mentioned it, not that he spoke about her much these days. Not without getting all evasive or soppy.

Rain pattered on the yellowing paper and Faye looked up to see the sky was a shade of indigo. It was Friday night. She was late.

‘Oh, buggeration!’ Faye jumped to her feet, clutched the book to her chest and dashed back into the tall ferns, heading for her bicycle, a Pashley Model A. She stuffed the book in her satchel and wedged the satchel in her bicycle’s wicker basket, then pushed away, gripping the handlebars. The Pashley was a boys’ bicycle – one she had bought second-hand from Alfie Paine after he gave up his paper round – and she had to swing her leg over the crossbar as she gathered speed.

As she was beetling over the old Roman bridge, she almost ran down a lad coming the other way with a trug full of elderflowers in the crook of his arm. Faye dodged around him as he jumped back with a cry of surprise. Faye brought her bicycle to a skidding stop in the undergrowth, sending the satchel flying. The book spun out of the satchel and onto the path.

‘Bertie Butterworth, what the blimmin’ ’eck are you doing skulking about in the woods at this time of night?’ Faye hopped off the bike and scooped up the book and her satchel, shoving them back in the wicker basket.

‘I’m, er, well, y’see, here’s the thing, I’m, oh, uh…’ Bertie was a little younger than Faye and had been soft on her when they were at school. Though Faye was sure he had a thing for Milly Baxter now, as he never stopped staring wistfully at her in church. He worked on his dad’s farm, which had given his cheeks a ruddy stripe of freckles and made his hair go as wild as a hedgerow. ‘I’m making elderflower cordial,’ he said once he got his words in order, proffering the trug full of berries. ‘Funnily enough, your dad wanted some for the pub.’

‘Dad?’ Faye squinted one eye as she wheeled her bicycle back onto the path. ‘Did he send you? Are you spying on me, Bertie Butterworth?’

‘Er, n-no,’ Bertie stammered. ‘I mean, yes, he sent me. To get the berries, that is, but I ain’t spying on you. I mean, I did see something moving about and I wondered if you were a, uh, a… well, no, it’s daft.’

‘No, go on. What did you think I was?’

Bertie leaned forwards, eyes darting from left to right, before whispering, ‘A Nazi spy parachuted in by the Luftwaffe to infiltrate the village.’

Faye looked up at his open mouth and sincere eyes and couldn’t help but snort a laugh. ‘You great loon. What would the Nazis want here?’

‘We have to be vigilant,’ he said as they walked together. Bertie did so with a limp, having been born with one leg shorter than the other. ‘They said it on the wireless the other night. If the Nazis invade, it’ll be right here.’

‘Well, there ain’t no Nazis here. Just me and a few squirrels.’

‘And a book.’ Bertie tilted his head to get a better look at the contents of the bicycle’s wicker basket. ‘What’re you reading?’

‘Nothing.’ Faye tucked the book behind her satchel. ‘An old recipe book. I’m thinking of making a jam roly-poly, if you must know.’

‘Oh.’ Bertie looked satisfied with the explanation, but Faye could sense the cogs turning within and any moment now he would ask why she had come to the middle of the woods to read a book. She had to change the subject.

‘You ringing tonight?’

‘Oh blimey,’ Bertie said, his face dropping. ‘What’s the time?’

‘Late,’ she told him. ‘Hop on. I’ll give you a backie.’

Still gripping the trug, Bertie clambered onto the saddle behind Faye, and she leaned forward on the pedals as the rain fell heavier. Faye was cross at herself for letting so much time pass unnoticed, but she had found a book of magic spells written by her own mother. The first chance Faye got, she was going to have to try one.

2 THE SOUND OF ANGELS

The first written mention of Woodville Village is in the chronicles of Wilfred of Cirencester, a travelling scribe sent by Offa, King of Mercia, to assess his new lands. Wilfred passed through the village in AD 762 and described it as ‘well past its prime, and in need of a good scrub,’ and the inhabitants as ‘dim to the point of savagery’. These were Wilfred of Cirencester’s final writings, found in a ditch with a few of his bloodstained belongings not two miles from Woodville.

Around the village, travellers might encounter dense woodland, several farms, a handful of mansions, a few ancient forts, an aerodrome, rolling downs, crumbling chalk cliffs and shingle beaches. The Wode Road is the only way in or out, and few come here by accident.

Faye pedalled hard up the Wode Road with Bertie perched on the saddle behind her, clinging to her back and his trug of e

lderflowers. The rain was pelting down and Faye hoped it would clear up before closing time tonight. She had promised to join Mr Paine on ARP patrol after the pub closed and she didn’t much fancy getting too cold and wet in the dark. They passed the grocer, butcher, baker, post office, sweet shop, tea room, general store, three pubs, a school, a library and two churches.

Saint Irene’s Church was by far the oldest of the village’s two churches, the other being Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, a relative newcomer built in 1889. The nave of Saint Irene’s dated back to the sixth century and was built with Roman bricks and tiles salvaged from a church that once stood on the same spot. Other nooks and crannies were added over the centuries, the final addition being the bell tower in 1310. The church was named after Saint Irene of Thessalonica, who was martyred along with her sisters for, among other things, reading banned books. Irene’s sisters were executed, but she was sent to a brothel to suffer molestation by the patrons. No one touched her in the end, and the story goes she converted many of the brothel’s patrons to Christianity with her passionate readings from the Gospels. Another story says the very same readings drove them to frequent another brothel up the road, but either way, Saint Irene’s stubbornness inspired the villagers to this day. No one ever brought up that she was burned alive as punishment for her refusal to compromise, but the villagers of Woodville weren’t the sort to let a grim ending dampen a good story.

‘Off you hop,’ Faye told Bertie as she brought the bike to a stop.

‘You go ahead,’ he said, stretching his uneven legs. ‘I’ll catch you up.’

Faye leaned her bicycle against the foot of Saint Irene’s bell tower, ducked in out of the rain and scuffled up the uneven stone steps of the spiral staircase. She could hear the voice of the tower captain, Mr Hodgson, preparing the other ringers for their final course of Bob Doubles. ‘Look to!’ he cried. Faye peered through the narrow stone arch into the ringing chamber as Mr Hodgson took hold of his sally. ‘Treble’s going…’ He pulled on the sally, bringing his bell to the balance point. Then, as it tipped over to ring, he added, ‘And she’s gone.’ The treble bell rang, followed in quick succession by the others.

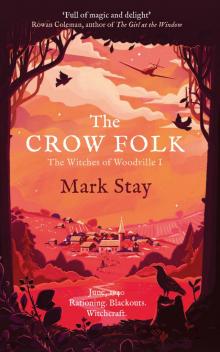

The Crow Folk

The Crow Folk